Looking for problems

A while ago, I wrote about how I'm starting a business and with which criteria I'm entering that journey. A month has passed, and I wanted to give an update on that!

Specifically, I want to share why I'm deliberately not building anything right now and how I'm approaching this business venture a lot more intentional than previously.

Because this won't be my first rodeo. I've started four businesses before; a gaming company, a web agency, a SaaS for TV series, and one doing online coaching. I count about half of them as successful, if the sole criterion is being profitable.

What I'm not satisfied with is how those came to be profitable — by dumb luck.

- When I ran a web agency, I "accidentally" specialized in a technology that became hotter than the sun at the time. I was just playing around with what I thought was fun, but still had to turn down clients every week because I had too much business.

- When I offered online fitness coaching, it started as a fun sidetrack to help others get in shape, while I was building my "real" product. Until one day I realized that the coaching was THE product.

If you've read about how I approach my reading list or my family's spendings, you'll know that I like structure and intentionality in my life. I love processes and systems that help me understand the world and reliably repeat success.

So this time, as I set out to build my fifth business, I want to understand it on a deeper level, execute with purpose, and hopefully feel more in control.

I imagine systems as levers, which can multiply the exchange between input and outcome. In the case of building a business, this applies to the work I put in versus the value I create for customers and the profit in my bank account.

In other words, the more systematic and intentional I approach this endeavour, the more value and profit I will be able to generate in the little time that I have to spare for it (after spending time with my family, doing a good job in my day job, pursuing my hobbies, etc).

More bang for less buck.

The horse before the cart

Fundamentally, a business is about solving a problem for someone, while yielding a profit in the transaction. That's market economy 101.

You find a customer segment with a common problem — and the buying power and will to solve it — to whom you offer a solution for a price. Simple!

The mistake that many fledgling entrepreneurs commit, including myself is to start with the solution. They build a product, spend months polishing and optimizing it, before going out to look for a problem that their product can solve. And then crossing their fingers that someone is actually willing to pay to solve the problem.

Let me be clear — there is nothing wrong with building for the sake of building! I encourage more people to work on side projects as a hobby! It's an excellent way to sharpen one's skills and explore new areas; I'd never been this good at software engineering if I hadn't had a thousand side projects.

However, it's important to be clear about what you do for fun and what you do for profit. There's certainly overlap but, as with any optimization problem, clarity in the end goal makes all the difference.

When your goal is to create value for end users and to profit from its provision, it's essential to know exactly what problem you're solving and for whom. You also have to make sure there are a sufficient amount of people suffering from this joint problem and that it's painful enough that they're willing to pay to have it solved.

You could create a thousand fantastic products but, if neither solve a real problem, you don't have a business.

But then how do you find a problem worth solving?

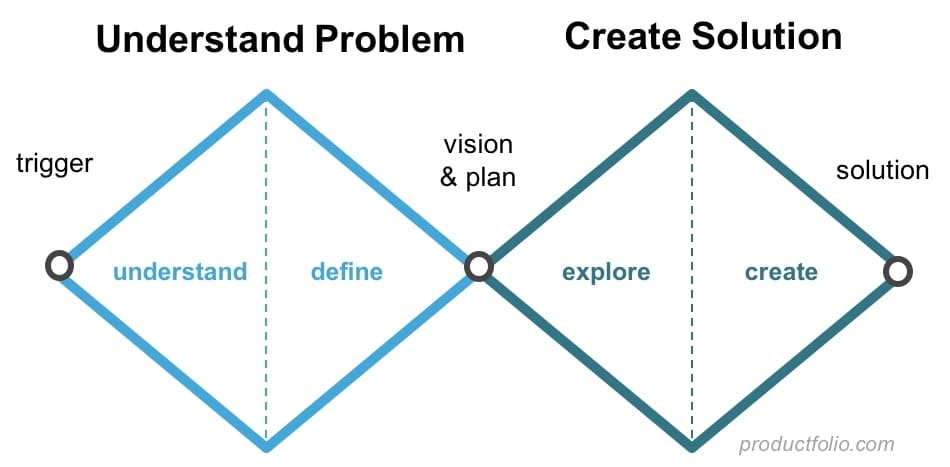

British Design Council developed a model for this work, which they call the Double Diamond. It describes a process where you first generate a host of problems (divergence) and then boil them down to the most important ones (convergence). This is then repeated for the solution.

(The Double Diamond is originally developed for a somewhat different context but I think it fits well here, as a conceptual framework. Diverge, converge.)

This model contains so much good stuff that isn't immediately apparent. Beyond the explicit prescription to focus on the problem before the solution, it also splits this work into distinct phases of generation and validation.

This is important, because if you only work on looking for problems, without later also validating and prioritizing them, you might as well just pick a random one or even just make a problem up.

Okay, fine. So how do you start to generate the list of potential problems?

Simple! By taking a step back, identify who you're trying to help, and then — gasp — talk to them. Your future customers know best which problems are giving them the worst trouble and what hurts the most in their own lives; you only have to extract that knowledge.

This is where I am right now: right in the beginning of my journey.

My next step

Luckily, I already know who my customer is. More or less, at least. They're a person responsible for the business side of gyms and similar health and fitness facilities — gym owners, facility managers, fitness business developers, etc.

I could of course dig deeper and complement with more demographics for my ideal customer and psychometrics for the buyer but, at this stage, that'd be procrastination.

Right now, I want to get to a point where I've identified a problem painful enough and developed a solution good enough that at least one customer asks me, "Can I please pay you for this?". That's my current goal.

To get there as soon as possible, I'm focusing on identifying and contacting potential customers, so that I can sit down and talk about the worst hurdles and hassles in their professional lives. I'm digging and learning, to better understand what I should tackle to enable them to help more people to health and fitness.

Thankfully, I don't have to do this completely clueless. I'm lucky to have stumbled over customer development geniuses such as Rob Fitzpatrick och Giff Constable, who have written gems like Talking To Humans och The Mom Test, respectively.

These two books teach how to structure exactly this type of interviews, analyze your findings, tweak your hypotheses, avoid the many pitfalls, and give a lot of concrete tips and tricks.

After having done a few interviews already, I'm so grateful for Rob's and Giff's works. I would never have learned as much or managed to facilitate as well without their collective wisdom. (Beer's on me if either of you ever visit Stockholm!)

Armed with this, I continue to work through my list of gym owners, one by one, until I've learned exactly which problems are giving them hell. Then it's time for the fun part — to see if and how I can solve the problems!

Curious to hear how that goes? Subscribe (for free) and I'll keep you updated!